Monitoring the Cryosphere’s Movement in the Rembesdalskåka Glacier

30 April 2025 - Writer: Pascal Egli

Rembesdalskåka is an outlet glacier of the ice cap Hardangerjøkulen in Southern Norway. Photo: Pascal Egli / NTNU

Our field trip to Rembesdalskåka at Hardangerjøkulen ice cap in southern Norway was completed by a team of three: Pascal Egli (Associate Professor at NTNU), Ursula Enzenhofer (PhD candidate at NTNU), and Inés Dussaillant (World Glacier Monitoring Service). The main objective of the field trip was to prepare Glacier Lake Outburst Flood (GLOF) monitoring devices for the summer, which we completed successfully.

More specifically, the aim was to read out data from timelapse cameras, replace batteries to re-install those cameras, install lake-water level (and temperature) loggers and stream-level loggers, measure the snow depth on the glacier tongue, install acoustic loggers to track the GLOF event for the first time, and re-install our temporary Automatic Weather Station (AWS) for the summer. These measurements provide data needed to calibrate and validate numerical models that try to reproduce the hydraulics and glacier dynamics of a GLOF event. Even without modelling, the data itself provides valuable information about the development of a GLOF event.

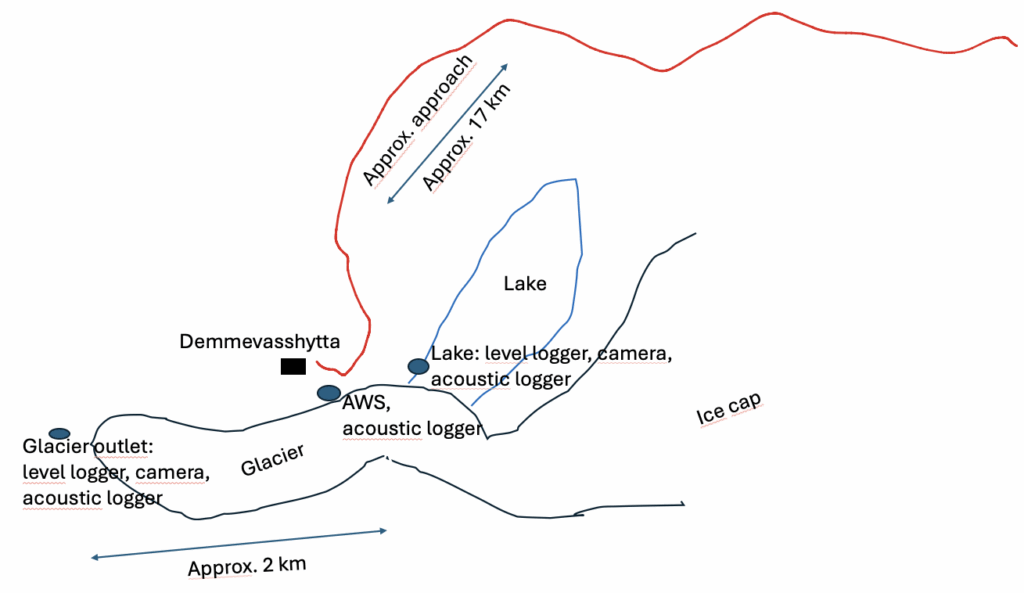

Data from lake-level loggers shows how many weeks it takes for the ice-dammed lake to fill up to its maximum volume of 2-3 million cubic metres, and it documents the quick emptying process once the GLOF event starts, draining the entire lake over just a few hours. The timelapse cameras add additional information about the type of drainage process, the state of the ice dam, and they can work as a backup in case the level logger fails to record anything.

The level logger and timelapse camera at the outlet of the glacier are also of crucial importance since they document the water discharge exiting the glacier towards the downstream hydropower lake. Comparing data from the lake-level logger and the logger in the outlet stream informs us about the time it takes the water to travel two kilometres through en- and subglacial channels to the outlet.

Measurements provide data needed to calibrate and validate numerical models that try to reproduce the hydraulics and glacier dynamics of a GLOF event – Pascal Egli, NTNU

The meteorological data provides context about conditions that prevail leading up to the lake drainage and prevailing during the drainage event. Such data helps us characterise what conditions may be responsible for the timing of the lake drainage. Finally, the acoustic loggers are experimental, and we try to use them to trace the propagation of the flood wave from the lake to the terminus of the glacier.

Fieldwork at Rembesdalskåka is never easy, as it is a relatively remote site. We brought food for four days, drove about seven hours across Norway and took a short train ride to Finse (1,220 metres, only accessible by train), where we stayed at the Finse Research Station. The next day, we were supposed to be driven most of the way towards the glacier in a snow scooter with the help of Jens Haga, Research Station Manager, but due to exceptionally warm conditions and little snow, water had entered the snowpack on the big frozen lake “Finsevatnet”, and it was difficult to cross it. Visibility was very bad, and we got dropped off at about 12 kilometres and 500 metres d+ (elevation) from our destination. We had to ski up and down with heavy backpacks and pull a heavily packed pulka for five hours to reach the DNT (Norwegian Trekking Association) hut “Demmevasshytta”, located next to our field site.

In the pulka and backpack, we brought tools, a drilling machine, glacier safety gear, avalanche safety equipment, food, batteries, and personal gear. We spent the afternoon preparing the AWS and other sensors, and the following day working in different locations on the glacier. It was important to start very early, as the sun came out and temperatures rose above zero degrees Celsius, increasing the risk of crevasse falls due to soft snow. On the third day, we skied back over a little mountain for 1.5 hours, now with lighter packs, and were lucky to get picked up and driven back to the Research station by our collaborator Jens Haga.